Directed by François Girard, the acclaimed director of The Red Violin, The Song of Names is a film hybrid. It melds mystery, music, history, and drama while crafting dynamic situations and characterizations. Jeffrey Caine (The Constant Gardner) adapted Norman Lebrecht’s prize-winning titular novel. Howard Shore wrote the original score, and the gorgeous music remains a vital character throughout. Especially at the concluding reveal, the music soars with beauty.

Set in London, the film jumps from 1985 to flashbacks to 1951 and 1939, and back to reveal a fascinating, poignant story about the 1951 disappearance of violin virtuoso Dovidl Rapoport, “brother” of Martin Simmonds.

At age 21, before a classical concert debut arranged by Martin’s father to launch his brilliant career, Dovidl disappears. Disappointed, Gilbert, Martin’s father, cancels the concert. Lords and ladies, critics, celebrated musicians and others receive their money back. Dovidl’s disappearance devastates Martin’s family. They search for him unsuccessfully and Gilbert dies months later, brokenhearted.

After 35 years Martin (Tim Roth) discovers that Dovidl may still be alive. Obsessed, he searches for clues to solve why Dovidl abandoned and humiliated them. During the course of Martin’s search, via flashback we learn how Gilbert (Stanley Townsend) accepted the nine-year-old Jewish prodigy Dovidl into his home and family to develop his genius.

On the eve of WWII, Dovidl’s father permitted his son to live with the Simmonds family while he went back to Poland to be with his wife and daughters. The Simmonds protect Dovidl and raise him under Orthodox Jewish law as best they can. As WWII breaks out, Dovidl and Martin grow close like brothers.

After the war, Gilbert attempts to locate Dovidl’s family, to no avail. Hurt, angry at God for doing nothing to stop the Holocaust, Dovidl renounces Judaism and God in a synagogue with Martin as witness. Embracing his brilliant career, he practices for his debut concert and assures Martin he will see him in two hours. Then, he goes missing.

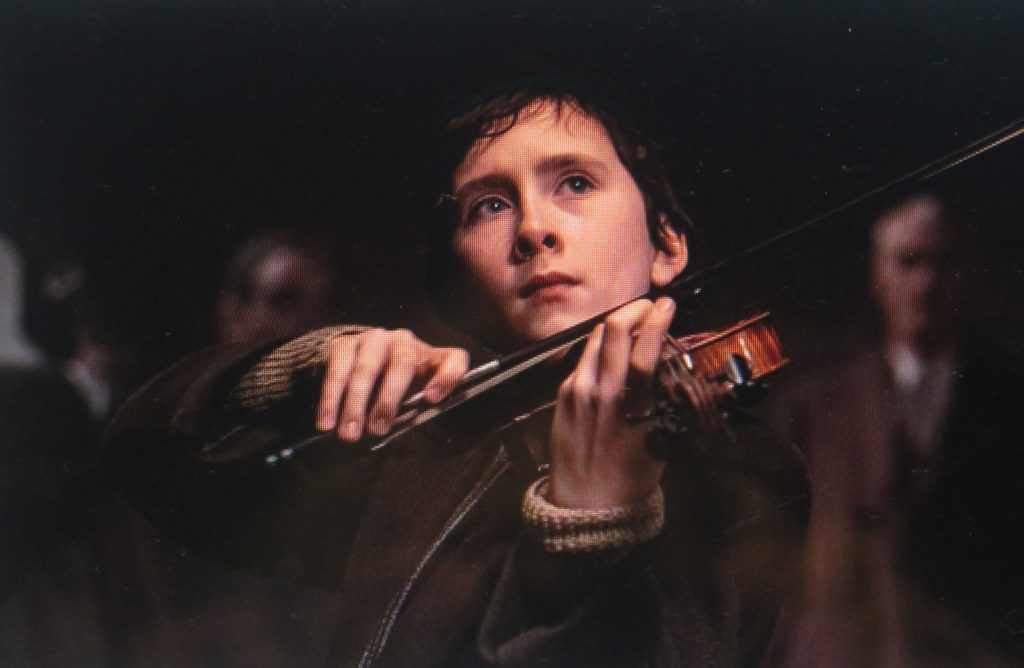

Director Girard’s division into the three time periods requires three sets of actors. As the 9-year-old Dovidl, Luke Doyle, an actual violin virtuoso, portrays the arrogant genius with authenticity. Misha Handley as his young counterpart Martin gives a sensitive, empathetic performance. The two youngsters provide the linchpin emotions and relationship that convincingly reveal the bonds of brotherhood. Because of the strength of their closeness we understand the adult Martin’s obsession with finding Dovidl. Also, Martin explains to his wife that Dovidl may need his help and he may be the only one to give it to him.

However, when Martin does find him, Clive Owen as the grown Dovidl astounds and shocks him with the profound truth of his decision to turn his back on Martin, the family and his career. The scenes between Owen and Roth are dynamic and suspenseful. Also, the way Martin uncovers clues to Dovidl’s whereabouts engages and enlightens. Gradually, we come to learn what Dovidl did and where he went instead of to the concert. Jonah Hauer-King and Gerran Howell portray the teenage Dovidl and Martin (ages 17-23).

The film emphasizes themes of faith, love, grieving, loss, and forgiveness, with historical references to Treblinka and the Holocaust. Cinematography, lighting and set design are spot-on. Importantly, the film memorializes a time 50% of people under 30 are unfamiliar with. Finally, the music score and the fine performances render this a film to see. Look for it in theaters 25 December.

Blogcritics The critical lens on today's culture & entertainment

Blogcritics The critical lens on today's culture & entertainment