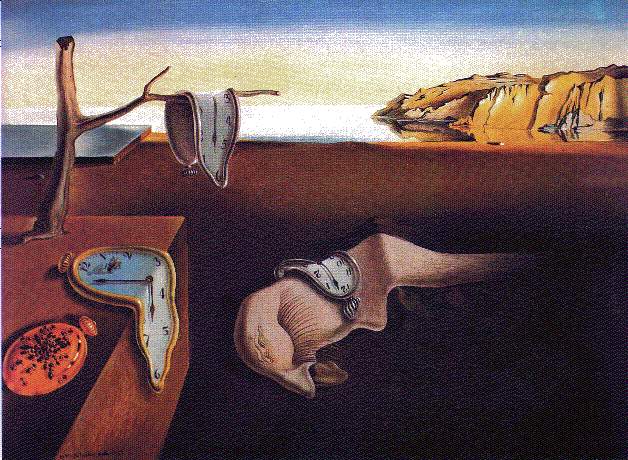

9/11 was an event of such magnitude that it altered time itself, sitting like a gigantic roadblock on the normally smooth procession from the past to the future.

I wrote the following on the 6-month anniversary of 9/11, on 3/11/02:

- The six months passed since September 11 seem paradoxically both a lifetime and the blink of an eye. September 11 is the day that “America was changed forever,” according to New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg at Monday’s six-month commemoration ceremony. There have been many perceived changes in America since then, involving geopolitics and political philosophy, mass culture and civic society, religion, ethics, semantics, and the nature of leadership. It is my contention, however, that the most profound post-9/11 change hinges upon our perception of time.

Our typical field of “time vision” is a few days: the immediate future slips steadily through the present into the recent past creating a small zone around our daily lives like a cocoon. For most adults, the intricacies of planning and executing a single day consumes the majority of our time-awareness: the particulars of work, family, personal finance, hobbies, and citizenship in a democracy not only fill our time, but add daily to a reservoir of things undone, always threatening to overrun its banks. This constant threat keeps most of our attention in the here and now.

No wonder so many of us have trouble sleeping, or even break down and abdicate all responsibility. “Time management” is based upon the very assumption that there is never enough time to attend to our responsibilities and interests – that the best we can do is to prioritize and “manage.” But the more we manage, the more constricted our view, the more “tunnel” our vision.

Many observers have noticed a certain excitement, even an odd euphoria in the air accompanying the grief, outrage, and fright since 9/11. It isn’t that we are ghoulish sadists just beneath our civilized exteriors; nor is it primarily the case that, as in the words of essayist Daniel Harris, “any crisis becomes a catalyst for instant togetherness … our fierce tribal instincts reemerge with a vengeance, having been thwarted by the curse of autonomy that afflicts advanced Western cultures.” Indeed, the opposite is more true: beneath the surface of our apparent autonomy, there is great community in our battle against time, our shared Herculean struggle to meet schedules and responsibilities to family, self, and society. There is even a communal sense of virtue in our acceptance of anxiety and not-quite-enough-sleep.

So, it isn’t longed-for community that generates the current buzz; it is the fact that the catastrophic events of 9/11 have shattered our work-a-day time vision, our little cocoons. There is a collective shiver of excitement as a strange new dichotomy has been created in our perception of time, away from a centralized, “time managed” here and now, toward the extremes of the very long and the very short.

This change in focus has been necessitated by our dual needs to comprehend, contextualize and assimilate 9/11 intellectually, forcing a long view of time on the one hand; and our need to scrutinize and document ever finer details of the horror in an effort to assuage our emotional pain on the other. By distributing the enormity of our pain (and guilt over surviving and/or not preventing the catastrophe) over an ever-larger, ever-finer series of moments, we seek to disperse it, to make it less dense and oppressive. We also, somewhere in the deepest recesses of our collective subconscious, hold out some hope that – counter to all intuition and every ticking clock – if time can be cut finely enough, perhaps it can be stopped or even reversed, giving us back what we had lost, returning us to an Age of Miracles.

There is abundant evidence regarding our change of focus to macro and micro views of time. Largely academic debates over the nature of the grand sweep of history have gained cultural urgency: the public is now familiar with Francis Fukuyama’s historical progress toward an “end of history” vs. Samuel Huntington’s perpetual “clash of civilizations, Benjamin Barber’s McWorld vs. Jihad and beyond, Robert Wright’s “non-zero-sum” evolutionary arrow toward greater complexity through cooperation. Robert Kaplan’s Warrior Politics, a survey of classical political and military philosophy, was a recent best-seller. The cover story of the current American Heritage is an explicit context-piece, “The Longest War,” Victor Davis Hanson’s lengthy treatise on the millennia-old struggle between East and West (he favors the West).

The evidence regarding new interest in micro-time dates to September 11 itself, when every telecaster with a tape machine and an antenna ritualistically ran images of the planes embedding themselves in the buildings, the effulgence of flames springing from the wounds, the subsequent implosion of the buildings, over and over again, burning them into the collective retina, focusing more attention on one sequence of events than any other in world history. (Only the Zapruder film of the Kennedy assassination even comes close.)

It was as if having recorded the monstrosity, somehow the results might be different on the 17th, 63rd, or 996th running of the tape: that perhaps if we s-l-o-w-e-d down the tape enough, we might discover an escape hatch between the frames, a tiny “Get Out of Disaster Free” card, Bugs Bunny’s “air brakes.” Stranger things have happened: according to the beliefs of 85% of mankind, God once created the universe.

Besides micro-interest in the event itself, there is intense general interest in “quantum weirdness,” including the indeterminacy of time at the subatomic level. If time is indeterminate, perhaps fate can be avoided. We can also draw some faint hope from philosophers, whose “tenseless” view of the universe (space-time as a whole does not change – change is represented by the relations of its parts) dates back to Parmenides in the 5th century B.C. Arguably, the most famous argument against time was presented by John Ellis McTaggart early in the 20th century

(Paraphrasing Savitt on McTaggert: 1 – there can be no time unless it has a dynamic element, that is, movement of an event from future to present to past; 2 – there can be no movement because the supposition that there is movement leads to contradiction. The contradiction alleged by McTaggart is that: for there to be movement, every event must have more than one element from between past, present and future, whereas, since past, present and future are mutually exclusive, no event can have more than one of them. This contradiction has been addressed by Seager, who asserts that these terms are mutually exclusive only at a given instant of time; they are not mutually exclusive over the course of time – a “time” that he audaciously asserts moves at the rate of one second per second. Take that, time bandits.)

Physicist Julian Barbour also concludes that time does not exist in his 2000 classic The End of Time, a position he summarizes thusly:

- “The quantum universe is static. Only timeless Nows exist. The quantum rules give them different probabilities. We experience the most probable Nows as individual instants of time. The appearance of motion and a flow of time are both illusions created by very special structure of the instants that we experience.”

According to Saunders in his review of The End of Time, Barbour

- ”embraces a ‘many worlds’ interpretation of quantum mechanics. Multiple worlds have been quite popular recently, and not only, as with David Deutsch (in The Fabric of Reality), to make sense of quantum mechanics. Physicists like Martin Rees (Just Six Numbers) and Lee Smolin (The Life of the Cosmos) use them to explain why the universe seems so user-friendly. Philosophers like David Lewis (The Plurality of Worlds) use them to account for our understanding of possibility. Barbour uses them to replace our idea of time. Time gives us a way to say things are different without falling into contradiction. Without time we must put things in different worlds instead.”

All of this work has been ongoing, but there seems to be redoubled urgency among the scientists and much deeper interest from the public since September 11. Just today in the NY Times, a substantial profile of the venerable physicist Dr. John Wheeler – who invented the term “black hole” – is headlined, “Peering Through the Gates of Time.” Headline editors get paid to know where their reader’s interests lie. It is a subconscious flicker of hope that the awful recent past may somehow be altered that causes our pulse to quicken when we read, in the words of Dr. Wheeler, that black holes teach

- “us that space can be crumpled like a piece of paper into an infinitesimal dot, that time can be extinguished like a blown-out flame, and that the laws of physics that we regard as ‘sacred,’ as immutable, are anything but…”

This leaves room somewhere for a “miracle,” whether it be religious, scientific, or both in origin. Wheeler also points out that

- even space and time [have] to pay their dues to the [Heisenberg] uncertainty principle. When viewed on very small scales or in the compressed throes of the Big Bang, what looked so smooth and continuous, like an ocean from an airplane, would become discontinuous, dissolving like a dry sand castle into a mess of unconnected points and worm holes …[called] “quantum foam.”

Imagine the look on the hijackers’ faces had they flown right through a Twin Towers made of quantum foam. Perhaps they might have caught a wormhole and ended up in their own assholes. It gives me great pleasure to picture Mohamed Atta spinning ineffectually around his own sphincter. Unlikely? Yes, but the existence of the universe (or universes) is much more so. Consider this:

- It is called double slit experiment. In it an electron or any other particle flies toward a screen with a pair of slits. Past the screen is a physicist with a choice of two experiments. One will show that the electron was a particle and passed through one or another slit; the other will show that it was a wave and passed through both slits, producing an interference pattern. The electron will turn out to be one or the other depending on the experimenter’s choice. That was weird enough, but in 1978 Dr. Wheeler pointed out that the experimenter could wait until after the electron would have passed the slits before deciding which detector to employ and thus whether it had been a particle or wave. In effect, in this “delayed choice” experiment, the physicists would be participating in creating the past.

In a 1993 paper Dr. Wheeler likened such a particle to a “great smoky dragon,” whose tail was at the entrance slits of the chamber and its teeth at the detector, but in between — before it had been “registered” in some detector as a phenomenon — was just a cloud, smoky probability. Perhaps the past itself is such a smoky dragon awaiting our perception.

The implications are obvious. Time is on our minds – but not normal, everyday time. We are looking to the great sweep of history to help us put the agony of September 11 in perspective, and to help us divine the future – a future we desperately want to go our way. We are also looking hopefully to the uncertainty of the infinitesimal with the unspoken longing that time is not a one-way street, that somehow egregious wrongs from the past can be righted, not in the hereafter, but in the here and now.

Time has moved on since 9/11, but have we? Or have we moved too far, already forgetting the elusive “meaning” that momentous tragedy seemed to yield? I try to hold the meaning that we are in this together in a carefully guarded box in my heart – it’s so carefully guarded I can’t always find it, but I found it today. I hope you are safe and well.

Blogcritics The critical lens on today's culture & entertainment

Blogcritics The critical lens on today's culture & entertainment