It takes more to writing an epic, it seems, than to just call it one.

Having finished reading an anthology of “epic” stories entitled, very bluntly, Epic, I must say that I am epically unimpressed.

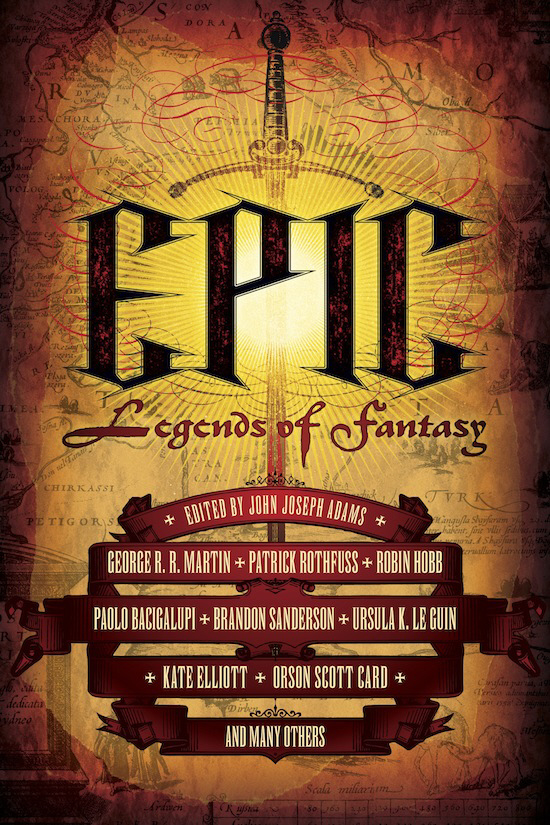

Epic, edited by John Joseph Adams, faces a natural and obvious challenge based on its very premise: the epic is a sweeping, grandiose genre, suited to cycles of lengthy tomes and thousands of lines of verse. It is hardly suited to short stories – not because genre is judged by length, but because it is nigh-impossible to develop the kind of magnificent world and larger-than-life story that defines a tale as epic within the word count naturally attributed to a short story or novella.

Naturally, the anthology’s editor tackles this problem before it’s even begun, quickly insisting in the introduction that the true epic is within the human heart, not defined by the content of a fantasy story. True, perhaps, but the problem is that however one defines the epic, in the end that definition only holds if the story itself evokes a feeling of awe and magnificence. A story is epic if it is grandiose, larger than life, and feels like it – and this quality, this atmospheric sense, is sadly lacking from this epically non-epic collection.

It should also be noted that few of these stories are redeemed by originality. There’s some pretty big names on the cover — George R.R. Martin, Patrick Rothfuss, Brandon Sanderson, Robin Hobb, Ursula K. Le Guin, among others — names, in fact, that drew me to reviewing this anthology in the first place. This magnificent array of fantasy authors have not written new stories, however: the tales in this volume are collected from other publications these authors have contributed to, or even from their novels. Some stories function better as standalones, some worse; some fit in better into a fantasy anthology, some worse. There is almost no unifying theme to these tales of fantasy, however, leaving the reader to judge them solely on their own merits of a fantasy story.

And, as such things tend to go, some are better, some worse.

The first tale, Robin Hobb’s “Homecoming,” is a lengthy but intriguing one, providing an exotic locale and a mystery tinged with horror. Though it hardly lives up to the title of the anthology it’s in, it is a strong story, drawing on those elements of storytelling that make good fantasy: worldbuilding, intrigue, and strong characterization in the midst of it all.

Ursula K. Le Guin’s “Word of Unbinding” has the simplicity and yet at the same time complexity of her Earthsea novels; there is something about her writing that always suggests the most complex ideas in the simplest of narratives, and this is yet another example. In contrast, Orson Scott Card’s “Sandmagic” is nothing but simplicity: the most formulaic of fantasy plots is condensed into a dozen pages, the whole thing reading like a Sparknotes version of the tale of Darth Vader who succumbed to the dark side for the wrong reasons.

Patrick Rothfuss’ “The Road to Levinshir” is as excellent as anything else he’s written. The problem lies in the fact that his story is an excerpt from his second novel, “The Wise Man’s Fear,” and functions much better as a set of chapters in a longer narrative than it does as a standalone story. It may have been published first, before Rothfuss’ own novel, but unfortunately that novel is what gives meaning to that story.

“Strife Lingers in Memory” stands out, however, as an important piece in an anthology of fantasy: rather than focusing on the typical heroic quests and mysteries and darkness and evil, it is the story about a fantasy hero’s PTSD; set after the events of an epic story rather than within them, it deals not with the prince becoming king or the warrior conquering a monster, but with the aftermath. Though short, Carrie Vaughn’s story shines in an anthology of unremarkable fantasy.

George R.R. Martin’s “The Mystery Knight” finishes up the anthology; like many of the stories in it, it takes place in the world he’s created for his novels — the world of Westeros — and though the tale’s well-told, it feels like an insignificant excerpt from his epic Song of Ice and Fire – a condensation, perhaps, of A Game of Thrones from a novel into a novella. It has his characteristic attention to detail and sweeping knowledge of history, but like Rothfuss’ excerpt, is much better understood by a reader familiar with his world, and would function better as an interlude in his saga than as a tale in an anthology.

Among these at-least remarkable stories are scattered ones much less noteworthy. N.K. Jemisin’s “The Narcomancer” and Tad Williams’ “The Burning Man” are not particularly remarkable in themselves, but they are not bad. In fact, they capture the imagination, but do little more. On the other hand, Aliette de Bodard’s “As the Wheel Turns” is simplistic and pointless, Juliet Marillier’s “Otherling” equally so. The rest of the tales are so-and-so – difficult, in fact, to say anything particularly interesting about, since the impression they leave is that of being unimpressive rather than outright bad.

In the end, the anthology leaves a general impression of insignificance, of momentary entertainment, perhaps, or diverting stories, but with hardly the impact and the power of tales that are truly epic.

Blogcritics The critical lens on today's culture & entertainment

Blogcritics The critical lens on today's culture & entertainment